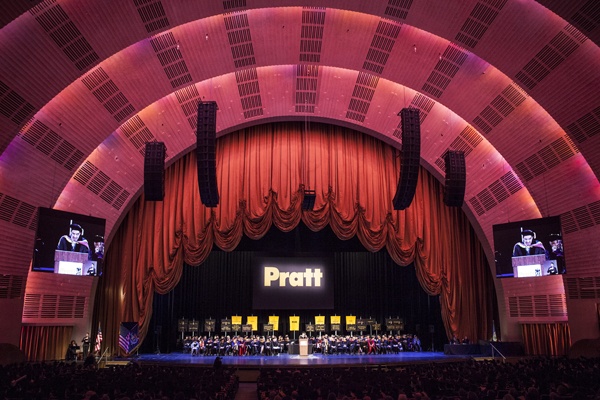

2013 Senior Thesis Awards in Critical & Visual Studies, Pratt Institute

5:09 PMThe faculty of the Department of Social Science & Cultural Studies is pleased to announce its Senior Thesis Award winners for Spring 2013! Congratulations to all of our Seniors!

Foundation for Graduate Work

Drohan J.W. DiSanto.

Catherine Frazier.

Residual Anxiety: On Fine Artists and the Market.

The recent emergence of violence in Guatemala's public sphere demands that we rethink both the reasons behind this violence and the future role of local and national conceptions of justice. This recent resurgence of violence speaks to the need to reclaim a commitment to human rights, especially in an environment ravaged by both “invisible” and “visible” forms of violence. The case of Guatemala is a powerful lens by which I will explore this dynamic. In this thesis I will show how the contemporary visual culture of violence in Guatemala is bond to the history of Guatemalans; specifically extralegal forms of violence that emerged in the country Guatemala during and after the civil war (1960-1996). I will explain why, after the civil war, linchamientos emerged as a new form of extralegal violence in indigenous Mayan communities in many parts of the countryside.

|

| http://static.tvazteca.com/imagenes/2011/25/Cronolog-linchamientos-926713.jpg |

Linchamientos are protests by means of “divine, sovereign” violence (Benjamin) to manifest existence. The shift of violence in the postwar years responds to a new form, for the state of exception to turn into a state of necessity, which can shift inhumanity into humanity. This is the notion of “crime as distinctiveness” that Snodgrass mentions.

The legacy of the Civil War as Snodgrass describes is mainly invisibility. Linchamientos make visible the space of the state of exception by its focus on the body. And for Agamben, these linchamientos embody a lacuna:

It is as if the juridical order (il diritto) contained an essential fracture between the position of the norm and its application, which, in extreme situations, can be filled only by means of the state of exception, that is, by creating a zone in which

application is suspended, but the law (la legge), as such, remains in force.

magnified. Guatemalan identity is a perforated concept. In her testimony, Rigoberta Menchú remembers us how the barriers between Mayan communities and ladinos has been instrumental for the elite class that runs the country, to keep the groups oppressed. Linchamientos express visibly the Mayan struggle towards recognition from the power apparatus; they embody the tension point with the state. On one hand, their exclusion is included by its own exception (Agamben); there is a resistance to the elimination of the state of exception. On the other hand, in the space that linchamientos create, there also exists a resistance to this resistance. The visual culture of linchamientos shows “the paradoxical nature of violence” (Girard) where evil and the one who combats evil are the same. It is as if violence came from without. In this regard, Agamben writes,

In the modern era, misery and exclusion are not only economic or social concepts but eminently political categories…In this sense, our age is nothing but the implacable and methodical attempt to overcome the division dividing the people, to eliminate radically the people that is excluded.

I will first examine the fallacies of the film and art-historical readings of Weimar cinema by Kracauer and Eisner to show how they have created a rigid and impenetrable “historical imaginary” of the films (as posited by Thomas Elsaesser.) This reading ultimately limits the potential of the films to be critically analyzed and understood in other ways, outside of locating some dark element in the German soul reflected in the films that foreshadows the rise of Hitler and the Third Reich. Then I will show how Deleuze’s appraisal of these films follows in line with Kracauer and Eisner’s readings, and that despite his call to “look in pre-war cinema, and even in silent cinema for the workings of a very pure time-image which has always been breaking through,” he himself never returns to the films (which sit firmly in his “classical,” pre-World War II grouping) to unlock the further potential they have within his own cinematic project and for cinema in general.

More exciting than the prospect of applying Deleuze’s already-made ideas and signs to a study of film’s history is the idea that the theory can be extended in new and previously un-thought of ways, which is already taking place contemporarily with both filmmakers and theorists advancing Deleuze’s ideas (mostly in the realm of digital and cyber video that is only touched on at the end of Cinema 2.) At the same time it is important to flush out the connections in early cinema as well, to gain the most complete vision of the time-image. The pure images of time and thought, the images that must be read as much as seen are the ones that Deleuze ends his books with. He feels these are the images that constitute the most cinematically engaged films of his time and will access new images later times. Yet he is always aware of the fluid nature of the cinematic signs he identifies; “from classical to modern cinema, from the movement-image to the time-image…it is always possible to multiply the passages from one regime to the other, just as to accentuate their irreducible differences” (Deleuze Cinema 2 279.) It is this subtle awareness in his own theories that makes it easier to suggest Deleuze did not miss a connection between the time-image and Weimar cinema but rather leaves readers with a vast number of open ideas to explore, images to connect, and concepts to furnish with the ideas he provides.

Foundation for Graduate Work

Drohan J.W. DiSanto.

0 comments